(Previous article: “All changed, changed utterly, the Easter Rising was born.” (Part 3))

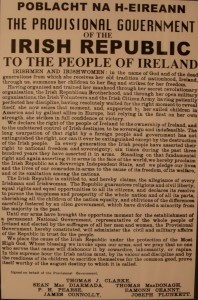

During Holy Week 1916, the seven-man IRB Military Council met to finalise plans for the Rising and draft the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. It is believed the literary composition, both expressive and heroic, is largely the work of Patrick Pearse. Subsequently, alterations were made by the other signatories including James Connolly whose socialist prose is inherent. The hand written, two page draft constructed by Pearse, was given to Thomas MacDonagh for safe keeping and handed to James Connolly at Liberty Hall on Easter Sunday for printing. The principal font for the document was provided by an English man, William Henry West. In Liberty Hall, early into Easter Monday morning.Under armed guard, Christopher Brady (armed with a pistol, given to him by Connolly), Michael Molloy and Liam O Briain printed some 1000 copies in two parts to be distributed across Dublin by Sean T O’Kelly after it was initially read out by Pearse (Kelly initially posed 2 copies to his mother and fiancée, knowing the significance of the document). The signing of the Proclamation by the seven members of the Provisional Government took place in the house of Jenny Wyse-Power. The honour of the first signatory was handed to veteran unrepentant Fenian, Tom Clarke, whom it cannot be argued was the brains and drive behind the Easter Rebellion. At the signing of the Proclamation, Thomas MacDonagh rose, faced Clarke, and stated, “You sir, by your example, your courage, your enthusiasm, have led us younger men to where we are today.” “No man will recede you with my consent.” Other members of the Military Council followed Clarke’s lead, thus, in essence, signing their own death warrants.

Shortly after noon on 24th April 1916, Patrick Pearse, President of the Irish Republic, dressed in the Irish Volunteer uniform with a green, soft hat, emerged from the now proclaimed rebel HQ, the GPO, flanked by his colleagues and read aloud the Irish Proclamation, declaring an Irish Republic. In the small crowd that gathered outside, some had “serious faces” listening intently, whilst others “laughed and sniggered.” In an act of solidarity, ICA leader, James Connolly clasped Pearse’s hand and passionately cried out, “Thanks be to God, Pearse, that we have lived to see this day.” To this day, that Proclamation as read at the beginning of the Easter Rebellion remains a revered, sacred and fundamentally important document for many.

The said document is perhaps the most widely recognised and significant text in Irish history. Its 487 words contain the first formal assertion of the Irish Republic as a sovereign independent state. The document is a call to arms, a mixture of fact and fiction, it links to history and mythology, outlines aims, aspirations and ideals, of hopes and ambitions of a greater more prosperous Ireland. Yet it was a progressive statement of intent which promoted a generous social and political vision for a new Ireland, an Ireland based on fairness, equality and social cohesiveness. When the seven man military council, to become the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic, signed their names under the Irish Proclamation, they demonstrated their commitment to its ideals by pledging their lives and their comrades to the freedom of Ireland and the right of the Irish people to govern Ireland. Many of the principles and values as set out in the Proclamation, today, remain a profound influence and are largely used to inspire what a future Irish Republic would encompass. But what is the meaning of this seminal document? Let’s deconstruct it.

POBLACHT NA H EIREANN …

POBLACHT NA H EIREANN are the only words contained within the Proclamation in Irish, apart from some of the signatories’ names. Although the word Poblacht did not exist in the language in 1916, the translation came to mean democracy or people government. It was a proclamation to the legitimate heirs of Ireland, the Irish people, declaring national Independence.

The Provisional Government of the Irish to the people of Ireland …

The Irish Proclamation is addressed to the people of Ireland, deemed as the rightful claimants of Ireland. Pearse’s reverence and unequivocal admiration for Robert Emmett is clear at the beginning of the Proclamation when he cites his 1803 Independence Proclamation, “The Provisional Government to the people of Ireland.” The Proclamation is aimed at the Irish people as the rightful owners of the country, whose government was dispossessed, with the aim of it being re-established in their name and for their common good. For the signatories, they believed they were acting on behalf of the Irish people, a sleeping giant. The leaders were extremely concerned about the condition of Ireland, pre-Rising, that Britishness had superseded Irish Nationalism and patriotism. They wanted to save Ireland before it was too late. Tom Clarke believed that a “fight would save the soul of Ireland.” Sean MacDermott repeated Clarke’s sentiments when he stated, “if we hold Ireland for a week, we will save Ireland’s soul.”

Irishmen and Irish women ….

The proclamation immediately makes reference to “Irish men and Irish women.” This was a very progressive statement at the time in that it gave formal recognition to women as equals in an inclusive Irish Republic. This at a time when women did not have political rights in many countries and whilst the suffragette movement was engaged in violent rhetoric to achieve their aims. Kathleen Clarke in her memoirs stated: “When it was signed it represented the views of all except one, who thought equal opportunities should not be given to women.” Today, that secret remains unanswered as Kathleen stated, “My lips are sealed.” Throughout the revolutionary period, women played a key role. They fought alongside and offered valuable assistance in the GPO (and other locations), alongside fellow men and were key in the struggle ahead. A direct connection to religion was almost unavoidable in a public proclamation (like the Ulster Covenant). “In the name of God”, an appeal to the most high at a time when time when Ireland was a very religious country. This would have appealed to those of that persuasion and justified in some minds the “just cause” nature of the Rebellion. A number of the signatories and even those who took part during the Easter Rebellion had strong religious convictions. A direct link to the “dead generations” illustrates the continuation by these men of the fight for Ireland’s independence. The dead generations refers to those who fought and died for the Irish nation, invoking their memory to inspire the current generation. The Easter rebels hoped to keep alight the flame lit by the dead generations, and the call from Mother Ireland to “Summons her children” refers to all those with a link to Ireland, young and old to rally to the cause, to answer that important call. To “strike for her freedom” implies the use of violent insurrection to achieve the set-out aims of establishing the independence of Ireland.

Having organised and trained ….

It is implicit in the second paragraph that the revolution seems to have come at the ideal time. The IRB, the IVF and the ICA are emphasised as the organisers and planners of the Rebellion. “Having perfected their discipline” illustrates how prepared and organised they feel they are. “She now seizes the moment” indicates that this was the right time to strike, with Britain pre-occupied with World War One, the Nationalist psyche, “England’s difficulty would be Ireland’s opportunity.” The support and recognition of America was important – American being key to the Irish Rebellion. “Exiled Children” refers to those who emigrated during the Famine, those members of Clan Na nGael, those who had to leave Ireland due to the abhorrent nature of British rule in Ireland. America had done so much previously for Irish revolutionaries, the Fenians in the 19th century sending money, sending support, sending weapons. America was seen as a country that could become Ireland’s greatest weapon in the fight against British rule. The reference “gallant allies in Europe” elevated the Rebellion to a higher level in the minds of the British and during their trials was enough to sign the death warrants of the leaders. The reference is obviously to Germany, although it remains unnamed in the Proclamation. Roger Casement and Joseph Plunkett had both spent time in Germany trying to procure weapons and military assistance for the upcoming Rebellion. The Germans had supplied 20,000 weapons for the Rising but had also supplied the UVF with arms during the Home Rule crisis. It was thought in the event of a German victory in World War One that Ireland would be independently recognised and part of the peace negotiations that preceded the War. Ireland “relying on her own strengths, strikes in full confidence of victory” was a fantasy. Historians have often argued over the chances of success. The leaders knew when setting out on Easter Monday there was no chance of victory, only the question of how long they could hold out. Just 1,500 rebels participated in the Rising. The loss of the Aud, the countermanding order by Eoin MacNeill and the military incapability of the rebels doomed any small chance there was of success during the Rising.

We declare the right of the people of Ireland ….

In the third paragraph of the Proclamation, the vision for Ireland and the rationale for the Rebellion is outlined, the principles on which the Proclamation had been founded and the right which has been asserted in arms. The “right of the people to ownership of Ireland” was crucial for the Irish people as land had been a major issue since the plantations of the 17th Century, through the times of the penal laws, famine and the land wars of the late 19th century. Irish people controlling Ireland would allow them to control its own destiny. Within this paragraph we clearly see Connolly’s socialist influence, “the right” of material distribution. The second “right” refers to “Unfettered control of Irish destines” illustrating that nothing short of complete independence from Britain is acceptable. The IRB, IVF and ICA were fighting only for a sovereign independent Ireland, for the Irish people, “Sovereignty” implying control of all moral and material resources of the nation, the nation being the people. “The long usurpation …” Links to history of heroic myth and sacred drama. The Rebellion’s leaders claimed legitimacy for their actions by arguing they represented the latest in a long line of revolutionaries who “six times during the past 300 years” have asserted Ireland’s right to freedom by the use of arms, this “Irish passion for freedom” that Pearse alluded to. The six times referred to, 1641, 1689, 1798, 1803, 1848 and 1867, it must be noted, were not all rebellions against England. Some were dynastic, civil or religious wars and could not be described as rebellion for independence from England. This implied 1916 was not a sudden, opportunist outbreak but part of a long established Nationalist tradition. “We had kept our faith with the past, and handed on a tradition to the future” wrote Pearse who didn’t see the Easter Rebellion as the final part of this tradition, he looked to future generation to keep the revolution going:“If our deed has not been sufficient to win freedom then our Children will win it by a better deed.” The authors of the proclamation then announced the newly established Provisional Government have proclaimed “the Irish Republic as a Sovereign Independent State.” The pledge that follows commits the lives of those involved to the struggle ahead for Ireland to not only put Ireland amongst the other nations of the world but to evaluate her to a higher place, to be exalted among the nations.

The Irish Republic is entitled to …

This section of the Proclamation is the most quoted and misquoted part of the Proclamation. The reference to “we” gives it a personal touch to mean collectively the Irish people. It is here that the Irish Republic is speaking and claiming the allegiance of every Irish man and women. The guarantees of the Irish Republic are clearly set out. The Irish Republic would ensure there would be protection of religious and civil liberties for all. Equal rights and opportunities would be afforded to all citizens regardless of their differences. An Irish Republic would be oblivious of the differences between nationalist and unionist traditions – all Irish men and women regardless of creed, colour, race etc would form part of an inclusive and pluralistic Irish nation. The Proclamation alludes to Ireland’s Protestant minority and points to England for promoting and fostering the differences between the communities: “The differences carefully fostered by an alien government, which have divided a minority in the past.” The Irish revolutionaries believed Unionists had been corrupted by the English and British influence. They believed this was not a natural state of affairs and the removal of this corrupt, alien government would allow Unionists and Nationalists to join together. The signatories to the Proclamation used these progressive concepts as a statement of goodwill and honest intentions, that future generation could use as a foundation to be built upon, however far fetched they may have seemed at the time.

Until our arms have brought the opportune moment …

The use of violence is justified here in that it aims to establish a “permanent National Government” that would be representative of all shades that encompassed the Irish people. It is clear the signatories envisaged a National Government with universal inclusivity, including a role for women in electing and participating in that Government. This Government would serve all the people, represent all the people and act on behalf of all the people of Ireland.

We place the cause of the Irish Republic

The final paragraph of the Proclamation, like the first, makes a reference to the “Most High God” for blessing on arms and the forthcoming Rebellion, believing God would favourably take their side. This would have been common practice, believing the intentions were of a just cause and in line with religious and moral beliefs. Patrick Pearse did not see the act of rebellion as evil. He justifies this when he states: “There are many things more horrible than bloodshed, and slavery is one of them.” “Slavery” reflecting the conditions the Irish people endured due to English rule in Ireland. The act of “sacrifice” something quite unique to Pearse with his notion of “blood sacrifice” are inherent in the final wording of the document. This “sacrifice” it would seem, would all be worthwhile in Ireland’s fight for freedom and independence.

The Proclamation expressed the hopes and aspiration of the revolutionaries. It was the first formal assertion of the Irish Republic as a sovereign independent state. The term “Republic” is used five times in the document, illustrating the type of Ireland the signatories had agreed and thought best for the Irish people. The actions and sacrifice of the leaders and rebels helped implant the goal of a Republic as a future national aspiration of the Irish people. The Proclamation portrayed an Ireland that physically never existed, but in the minds and dreams of the signatories to the Proclamation, it would. The ideals, principles and objectives as espoused in the Proclamation, 100 years on, have still not succeeded. Will they one day?

Beautiful, Ciaran.

It is within the hands of the people of Ireland as to when an independent Irish Republic is achieved.

I for one would give up my life to see that republic fulfilled.

Yes indeed Ciaran ,beautifully composed piece and in reading it my mind drifted to those harrowing , nightmarish days of the Hunger Strike….we were ,mentally , at a very low ebb…. but we carried on and gained strength from our combined sadness to become a real and imminent threat to all those revisionists ,those West Brits ,those nay-sayers …those pseudo intellectuals …. It’s not in their remit to opine as to who is , or is not , a good Irishman/woman….to question the validity of 1916 , to question the motives or methods of those genuinely seeking to establish an authentic 32 county , republic. We will have our day in the sun ,not in spite of them, but because of them !

Outstanding Jude. Brilliantly analysed. Keep up the good work.

Grma, Mitchel. But not me, alas – all credit to Ciaran Mc…

“Since the wise men have not spoken, I speak that am only a fool;/…never hath counted the cost,/…For this I have heard in my heart, that a man shall scatter, not hoard/…O wise men, riddle me this: what if the dream come true?/…Do not remember my failures,/But remember this my faith.” An Phiarsaigh

Remarkable!